In-depth: Why Snowboarding Is Embracing Three-Dimensional Base Design

For years, three-dimensional bases were a niche idea in snowboard design. So why is that changing now? Tristan Kennedy investigates.

There’s a story that the Co-Founder of Netflix, Marc Randolph, is fond of telling, about a meeting in the year 2000 with top executives from Blockbuster Video. The confirmation had come in late, so Randolph had to fly straight from a booze-fuelled company retreat. He was feeling hungover, overwhelmed, and distinctly underdressed, in his California tech-bro uniform of shorts and a t-shirt. Still, he thought Netflix, who were asking for investment, had a pretty good pitch. But when he and his colleagues laid out why they thought the internet would revolutionise video rental, the smart-suited Blockbuster executives basically laughed them out of the room.

Around the same time, a Norwegian named Jorgen Karlsen was trying to explain to representatives from several big-name boardsports brands why his patented idea – for a snowboard with a three-dimensional base – would change the industry forever. Like Marc Randolph, Karlsen didn’t look the part. He wasn’t even a snowboarder, his background was in biophysics. In meeting after meeting, the biggest players in the snowboard industry gave his ideas similarly short shrift.

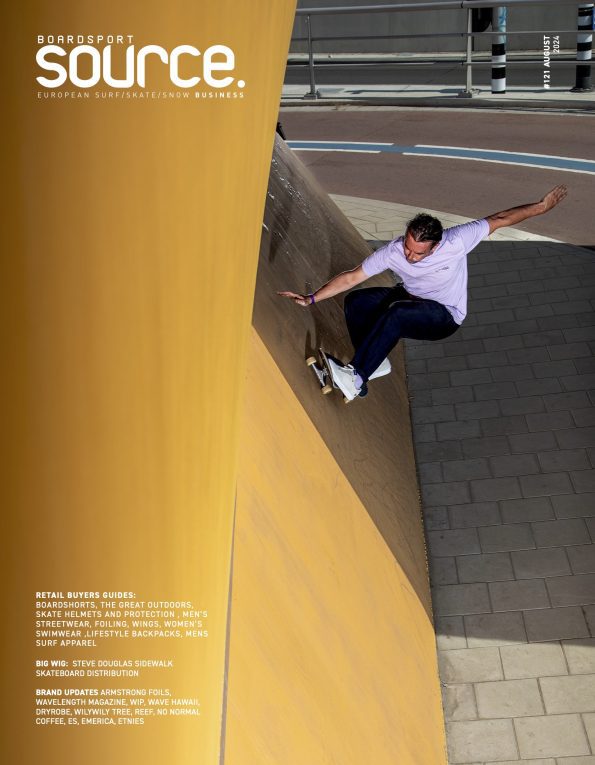

Bataleon

Karlsen, however, was undeterred. In fact, he was so convinced that his idea, which he called ‘Triple Base Technology’, would work, that he set up his own company, Bataleon Snowboards, to prove it. “As well as being one of the smartest guys on the planet, Jorgen is also one of the most stubborn,” says Danny Kiebert, now the brand’s Creative Director. Over Zoom from the Netherlands, Kiebert explains that although Karlsen is no longer involved in the day-to-day running of the brand, his patented ideas still underpin every board they make. Karlsen’s idea might not have revolutionised the snowboarding world straight away, but if you look at recent design developments across the industry, it’s hard to escape the impression that, like Marc Randolph of Netflix, the Norwegian maverick was right all along.

Preaching the 3D Gospel

In the last five years, snowboard companies have been falling over themselves to make boards with three-dimensional base profiles. Yes Snowboards launched their ‘Powder Hull’ shape four years ago, and updated it again last winter. Their sister brand Jones Snowboards now features ‘3D Contour Bases’ on most of their range, and this winter they added it to a splitboard for the first time. Three-dimensional tech is increasingly being used on park and all-mountain boards too. Arbor, for example, have been including ‘Uprise Fenders’ on all of their camber snowboards since 2016, while last year, Burton’s Fish 3D, a three-dimensional update to their legendary powder board, was joined by the Kilroy 3D, a park board.

None of these, to be clear, is a direct copy of Jorgen Karlsen’s original idea. “All of these guys are aware of our patent, and respectful of it,” says Danny Kiebert. But while each of these companies puts their own, subtle spin on three-dimensional bases, the basic principle is the same: by lifting the edges of the board, particularly around the contact points near the nose and tail, you make them harder to catch. This makes the board easier and more forgiving to turn, and also helps it float in powder. Karlsen’s genius, according to Kiebert, came in realising that “you have to shape the snowboard to the shape it will take when all pressures are applied to it”. Despite not being a rider himself, “he figured out what the correct shape of a snowboard should be.”

Unfortunately, the rest of the industry wasn’t quite ready to listen to a crazy Norwegian with no snowboarding experience. “For years, people looked at Bataleon snowboards and were like: “‘that’s weird’,” says Danny Kiebert. Conventional wisdom held that rocker, introduced to the masses with the launch of the Lib Tech Skate Banana in 2007, was a better way to achieve that ‘catch free’ feel.

“I get it,” says Kiebert, “our shape is much harder to understand. And say what you like about rocker, but calling it a banana is genius. It’s way better than calling it ‘Triple Base’.” At the time, Bataleon and their acolytes were telling anyone who would listen that these ‘reverse camber’ boards, by definition, sacrificed some of the pop and stability you get from a traditional camber profile. But with rocker boards disappearing from shop shelves quicker than free beers at ISPO, these arguments largely fell on deaf ears.

Burton

Word gets around

Yet although Bataleon were the only brand who fully committed to the three-dimensional shape for over a decade, they weren’t the only people ever to have dabbled. According to Scott Seward, a Senior Design Engineer for Burton, Jake Burton was “prototyping and building boards with convex bases as far back as the 80s,” and even Kiebert is careful not to claim that his company invented the concept outright.

“Any time you claim you were the first, someone will dig out some guy who built some board back in the day,” he says. “Like we met a surf shaper in California called Bill Stewart who was putting bevels on his longboards, and he made a snowboard in ’81 [with something similar]”.

What is beyond doubt is that Bataleon’s steady growth helped make these fringe ideas more palatable, but there were other factors at play, too. The way people ride has changed significantly since the mid-2000s. Carving has come back in a big way, the Yawgoons have spawned a thousand imitators on Instagram, and a whole new generation of riders have decided that, actually, camber was a good idea after all.

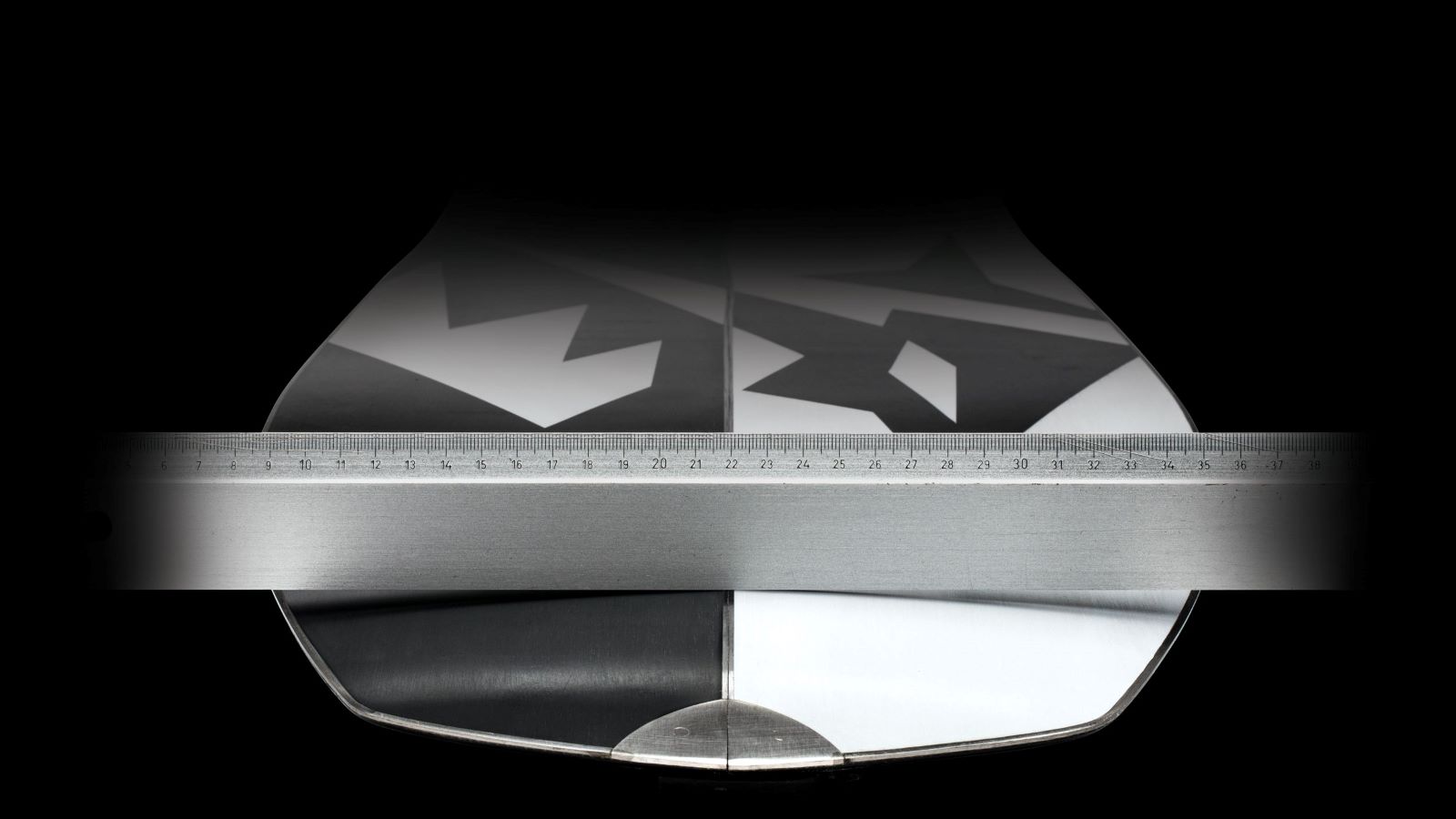

Investments in new tech and manufacturing processes have also been key. Making a board that’s not a conventional camber or rocker shape requires not only moulds, and in some cases, a whole new set of finishing tools. While Bataleon’s three flat base sections can be ground down using conventional tools, other more rounded shapes present greater difficulties. “You can’t grind these boards, or sand them, or wax them for snow, like a conventional board,” says Scott Seward of Burton. “It’s been a huge job working out our manufacturing process so we can keep the prices down. Without giving away too many trade secrets, we’ve created tooling and machinery that allowed us to quickly change components without having to change the entire setup,” he explains.

Xavier Nidecker, of Jones Snowboards, explains that they’ve also had to put a lot of time and effort in making their three-dimensional bases, which feature a continuous curve inspired by surfboard shapes. Their splitboard versions, introduced this year, have been particularly complicated. “It’s one of the biggest engineering challenges we’ve ever faced,” he says. “A 3D splitboard mould is a work of art compared to a simple 2D snowboard mould. We made dozens of prototype[s] before we got it right”.

An end to trends?

Perhaps the most important shift driving the new-found enthusiasm for three-dimensional bases, however, is not a rider-driven trend, but a change in the industry’s attitudes to trends full-stop.

It wasn’t just the fact that Jorgen didn’t look the part which made him stand out, according to Danny Kiebert. “He basically took a hardcore scientific approach to [snowboard design]”. This, Kiebert says, is the opposite of the industry’s normal way of doing things, which is just “trial and error”.

As much as snowboarding would like to consider itself an open-minded industry, when it comes to promoting new ideas, companies are often better off paying for the endorsement of a big-name pro than they are pumping money into genuine R&D. To get something to sell, Danny Kiebert says, “you just need to get the right people to go ‘sick, bro’.”

That’s not to say that big name pros and genuine R&D are mutually exclusive. Some of the most interesting ideas around 3D snowboard design in recent years have come from Slash Snowboards, run “as a one-man army” by none other than Austria’s Gigi Rüf. When I reach him in his home office, he digs out cardboard models, sketches and prototypes he’s been working on recently, delving into detailed descriptions with a boyish enthusiasm that’s so infectious it cuts through despite our dodgy Zoom connection. But as we talk through his ideas for “a sort of taco” style board, it emerges that even his efforts to push new tech has been stymied by people’s reluctance to consider new, outsider, approaches in the past.

Slash

“Ten years ago, in the early Slash catalogue, look, I had a technology called reactive flex,” he explains. The tech, developed by a tiny Austrian brand called Silbaerg Snowboards, used tension, and a particular kind of fibreglass layup. “When you bend the board in the turn, the base becomes convex, so the edges grip more, and the opposite happens when you get on a rail – it becomes a concave.” Unfortunately, when he was forced to move his production to another facility, this potentially revolutionary concept fell by the wayside. Silbaerg Snowboards still exist, but without Gigi’s buy-in, it’s hard to imagine their tech being embraced by the wider snowboarding world.

Hopefully, Kiebert says, attitudes in the industry are changing, and if a new Jorgen Karlsen was to emerge onto the market today, with an equally crazy-sounding idea, he would get a more receptive audience.

Whether or not three-dimensional bases are the innovation that finally convinces snowboarding to judge tech on its own merits, it’s an idea that’s here to stay. “I don’t think this will be a quick fad,” is how Burton’s Scott Seward puts it. “We’re going to be spending time and resources developing these boards, we’re not planning on stopping.”

As for Jorgen Karlsen, the man who did more than anyone else to set this ball rolling? He’s long since moved onto his next project. “You know how the biggest challenge in science is the Unifying Theory?” says Kiebert, referring to the discovery which would explain the discrepancies between quantum mechanics and Einstein’s theory of relativity. “Well, Jorgen now has a theory. He’s working with mathematicians from the Ukraine to prove it. You laugh, but that’s what he’s doing now.”