The Evolution Of The Snowboard

How’s this for a headfuck: According to recent studies, the average smartphone user touches their device 2,617 times every single day. If you’re particularly active (you’ve just posted a shit-hot ‘gram, say, and you’re watching the likes roll in) this can rise to over 5,000 clicks, taps and swipes. In total, we spend three to four hours each day glued to our smartphones. Such is the pace of technological change that a device which didn’t exist twenty years ago now monopolises more than a quarter of our waking life. By Tristan Kennedy.

SOURCE illustration

Cast your mind back further, to when snowboard manufacturing started, and the differences are even more stark. If you were to travel back to 1977 for example, the year when the late, great Jake Carpenter started putting out boards under his middle name, you may not have been able to read this article at all.

Sure, you might have been able to find something like it in print but there’s no way you’d peruse it on a computer, let alone a phone. Microsoft (founded in 1975) was only two years old, Apple (1976) had just begun flogging those early beige PCs, and Mark Zuckerberg was still four years from being born.

The world of boardsports was similarly unrecognisable. In 1977, the Dogtown boys were just kicking off their urethane-fuelled, pool skating revolution, and a small Australian surf brand was starting to attract attention in the U.S., not least thanks to a new logo which combined a cresting wave and a mountain. Two years later, a young elementary pupil would earn an A+ for a school report entitled “The Roots of Skateboarding.” His name was Tony Hawk.

Yet, for all these seismic changes in design and tech, if you were to take a look at next season’s crop of new snowboards you’d be forgiven for thinking that the last 40 years had changed very little.

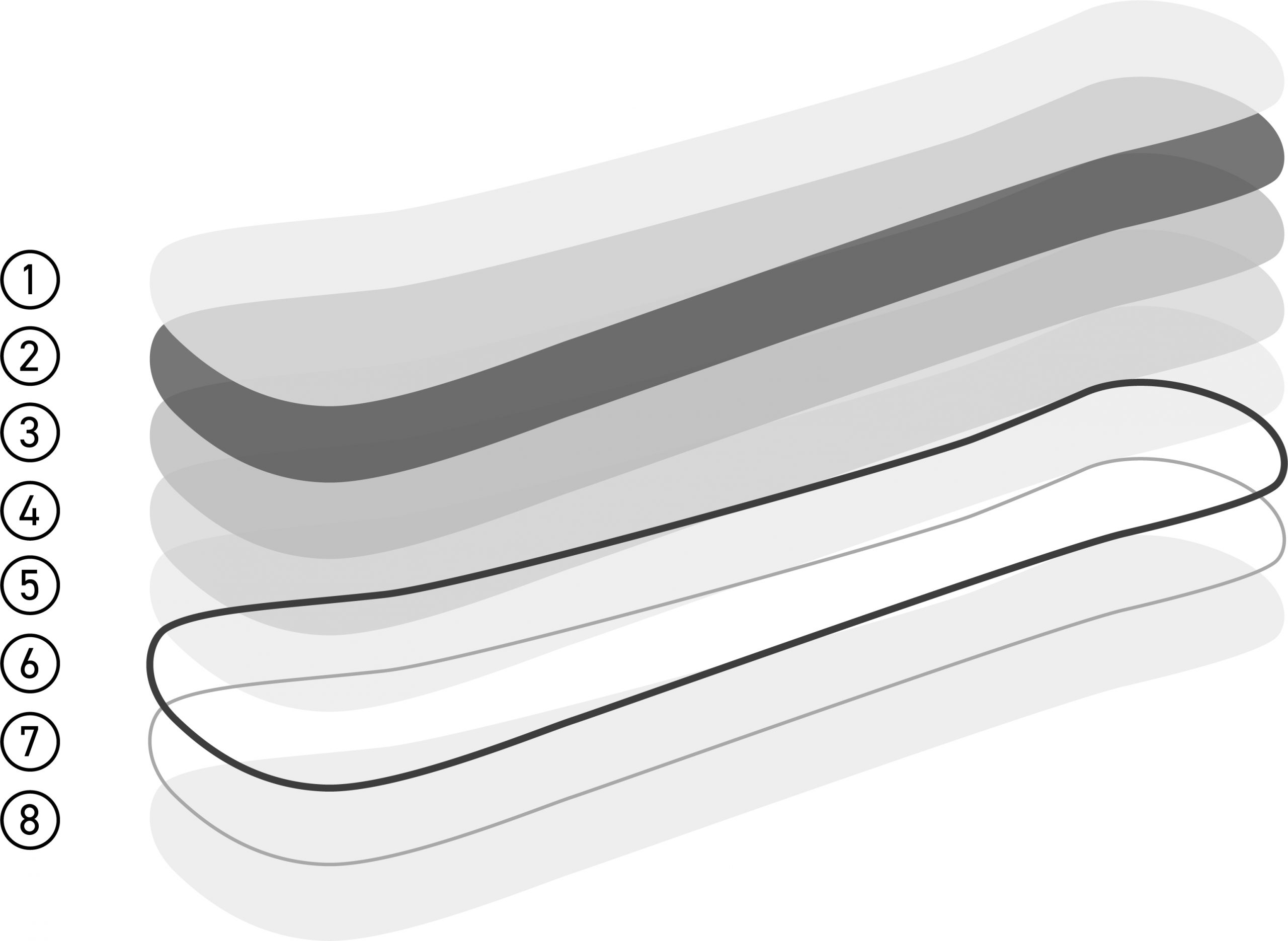

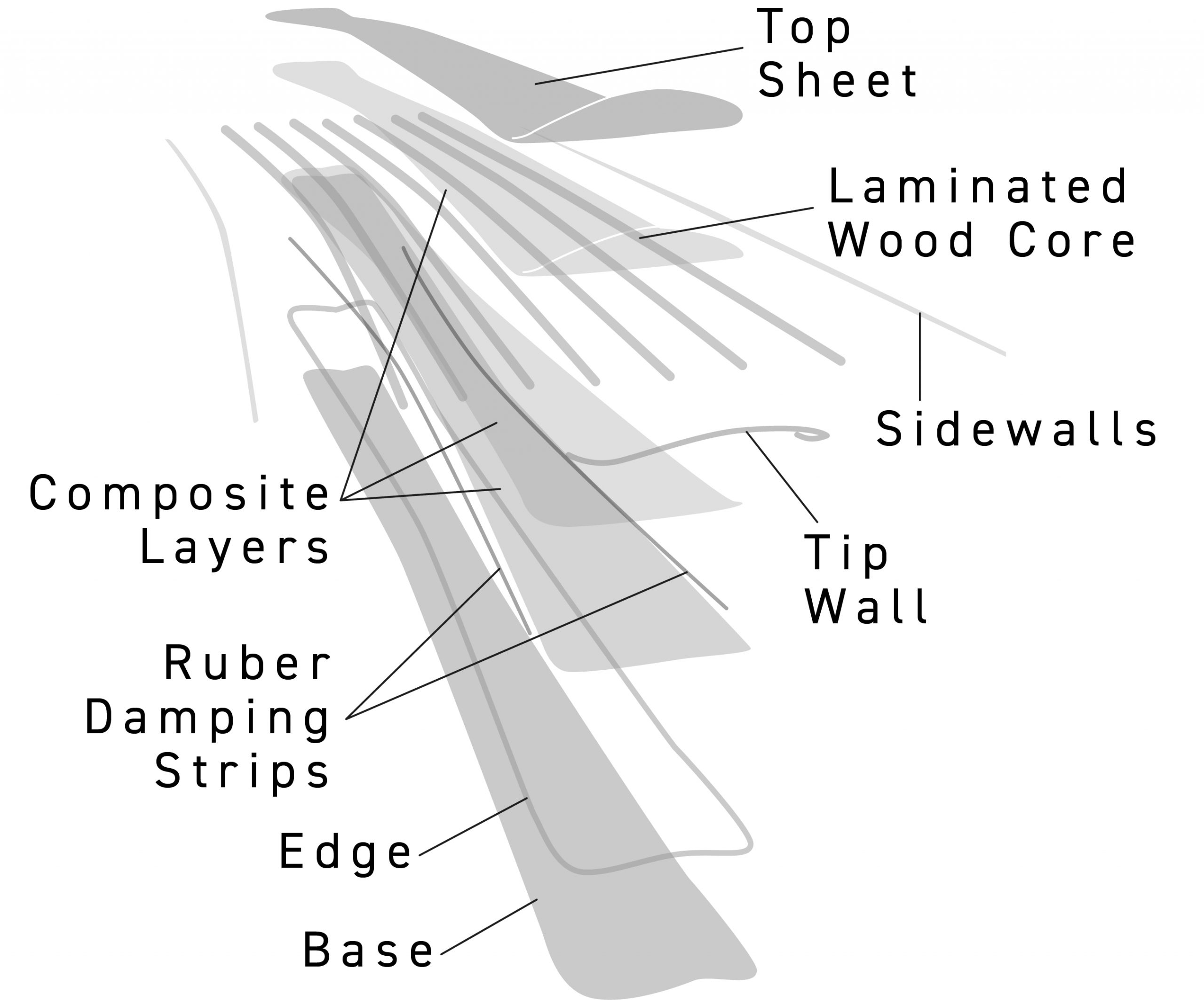

The manufacturing processes are largely the same, for starters. As Mark Dangler of Capita snowboards puts it, “the baseline act of how you build a snowboard hasn’t changed drastically” down the years. All snowboards are still built, at least in part, by hand. The basic materials are essentially the same too. “It’s still just fibreglass, resin, and wood squished together,” says Alex Warburton, designer for Yes Snowboards, and the man behind the 420, one of the most innovative models of recent years.

The most striking similarity, however, is the way today’s boards look next to the models that Jake, Tom Sims and Mike Olsen of Mervin were putting out in the late 70s and early 80s. Pointed noses, surf-inspired outlines and cutaway tails – things that were last considered cutting edge around the same time as Phil Collins’ mullet – are back, and in a big way.

As Warburton says, “the most interesting stuff people are riding today is closer to the designs of the 80s, certainly than anything happening 10 years ago.” Even a lot of the graphics are throwbacks. It’s comparable to Apple issuing their latest iPhone in an attractive shade of beige, with that original rainbow-striped logo on the front.

The story of how we got here, and why designers are going back to the future for inspiration, is a fascinating one, involving all three of snowboarding’s main geographical centres – North America, Europe and Japan. As each region has taken its turn at the cutting edge, it’s brought a unique cultural contribution to the design process.

Surfin’ USA

Thierry Kunz has had a ringside seat for many of these developments. Now Chief Marketing Officer at Nidecker, and the man behind their Snow.Surf collection, he’s worked in the industry for decades, including stints for DC and Quiksilver. He started snowboarding in 1982, when the first generation of boards began appearing on his home slopes in Switzerland.

“At the time, Sims was definitely more advanced than Burton,” he says, remembering an ‘82 Burton performer, and then two years later, a Sims Blade. It was “one of the first with edges,” and the board finally convinced him this new sport could replace skiing. It was still pretty basic however: “There was no highback on the bindings,” and “the fibreglass was not what it is today.”

In that early era, as brands battled to push R&D boundaries, many of their ‘new’ design ideas were straight from surfing. Thierry even remembers a Burton Cruiser he owned in the 80s, where “you had a metal piece with an angle that was like a fin on the bottom.” The feature was mercifully short-lived, but it indicates just how much those early pioneers looked up to their surfing forefathers. This was an era, after all, where Dimitrije Milovich, Founder of Winterstick, referred to his products as “Snow surfboards”, and the first ever US Open, held in the same year Thierry started riding, was known as the “National Snow Surfing Championships.”

“When those guys started out, they wanted to surf the mountain,” he says. They were more likely to have referred to it as “snow surfing, or snurfing,” instead of snowboarding. “It was all more surf-orientated.”

This began to change towards the mid 80s, when Tom and the Sims team that included Terry Kidwell started bringing skateboard tricks to the snow. Sims built his first kicktail board – designed to make switch riding easier – in 1985. That same year in Calgary, an oft-overlooked design pioneer called Neil Daffern, designed the first true twin board (which he released under the Barfoot name).

As freestyle spread, the pointed noses and fish-like tails that characterised early, surf-inspired board designs began to disappear, replaced by models that took their design cues directly from skateboards. By 1993, Sims had gone the whole hog, releasing the celebrated Noah Salasnek pro-model, with a base-graphic that featured trucks and wheels.

SOURCE illustration

Eurocarving, Ski Tech and the Need for Speed

But if the U.S. was embracing skate style, across the pond in Europe, a different set of influences was coming into play. Hooger Booger, a brand established by Swiss riders José Fernandès and Antoine Massy, was the first company to start building boards in Europe, in 1983. But others including Hot Snowboards, founded by French legend Serge Dupraz, and Nidecker, a venerable family-owned sports gear manufacturer that had been in business since 1887, swiftly followed suit.

What set these companies apart from their U.S. counterparts was their exposure to ski manufacturing techniques and materials, and their willingness to borrow them. “Things like kevlar, composite fibres, and 360-degree edges – it was the ski factories that had the knowledge of using all those materials,” explains Thierry, “and it was the Europeans who really took those ski manufacturing processes into snowboarding.”

A few key figures really drove things forward – Dupraz, a former skier who’d also learned how to shape surfboards on Hawaii’s North Shore, had a particularly unique skillset. It was he who first pioneered features like the asymmetric sidecut, which has enjoyed a renaissance of late, at Hot Snowboards.

It helped that in Europe, as on the East Coast of the US, snowboard racing remained popular throughout the 80s and well into the 90s. “It’s hard to imagine,” remembers Thierry of the era, “but in the early-90s to mid-90s in France, about 70 percent of the market was hard boots. In Germany, it was 80 percent.” There was a clear market incentive to make dramatic improvements to shave vital seconds off race times. The average weight of boards plummeted, and flex patterns became more sophisticated.

Learning lessons from the ski industry helped push the envelope in terms of build quality too. Previously, Thierry remembers, “bindings, they were like a gruyere, you know like a cheese. Holes everywhere!”

Cross-pollination with the ski industry would open up new frontiers for snowboarders everywhere. As Nitro Snowboards’ Co-Founder Tommy Delago explains, unequivocally, it was “only the adaption of methods and materials [from] the ski industry [that] made it possible for snowboarding to migrate from powder to hard-packed slopes.” But it was Europe that really drove this forwards. By the mid-80s, even Burton had started building boards in Austria, recognising that the old continent could bring something new to the table.

The Skate Takeover

Despite their impressive innovations however, the racers’ days were numbered. Snowboarding was booming by the end of the 90s, but the growth was all in freestyle, and while new brands were entering the market each winter, this didn’t necessarily translate into more creativity. If anything, it was the opposite.

Many of these new kids on the block were mass market sports brands, who saw snowboarding solely as a way to cater to a ‘youth’ demographic. “For them, snowboards were only for kids between the ages of 15 and 18 years old,” says Thierry. Prices needed to be kept low, so that kids could afford the product, and it quickly became apparent that the right graffiti-inspired graphic would shift more units than expensive R&D anyway.

It didn’t help either that Burton had enjoyed astronomical success with the Custom. To this day, it’s the best-selling snowboard of all time, and a brilliant piece of kit. But just as The Strokes had a part to play in inflicting The Kooks on the world, the Custom’s brilliance unfortunately inspired a whole host of average imitators. In helping popularise the ‘quiver of one’ – the idea that one board could do everything equally well – it convinced some lesser brands not to bother trying anything different.

Around the same time, manufacturing processes were becoming standardised, and board makers began outsourcing production to third parties. This lowered the barrier for entry, allowing everyone, from skate brands like Airwalk and World Industries, to ski companies like Atomic, to churn out the identikit twin-tips that flooded the bottom-end of the market.

Design progression stalled. As Alex Warburton remembers: “You couldn’t even deviate from a rounded nose and tail shape for 10 years, let alone mess with construction techniques. I think that was our dark age – not for riding, that part was going off – but just a complete dead zone for creative design thinking, right when the sport was at its peak popularity.”

SOURCE illustration

Japan to the Rescue

There are many reasons behind the snowboard industry’s dramatic tail-off in growth around 2010. The economic crash of 2008 obviously played a part, as did the growing popularity of freestyle skis (which meant fewer kids switching over to single-planks when they hit puberty). But as snowboard brands disappeared down a freestyle, twin-tip cul de sac, the part played by bad design can’t be discounted either.

Snowboards had become, quite frankly, boring. Aside from the spurt of innovation sparked by Mervin bringing back reverse camber and introducing Magnetraction and Bataleon coining the triple base, there was very little that was new or exciting. And with the snowboarding population as a whole getting older, the brash, trashy graphics weren’t cutting it any more.

The renaissance, when it arrived, came from an unexpected source. Japan had long been a big market for U.S. and European snowboard companies, but Japanese brands had never really made the leap the other way. Homegrown companies like Moss Snowstick, founded in 1979, and later, Gentemstick, had been making handmade boards for their more discerning domestic customers for decades.

Partly as a result of the consistently epic snowfall on Hokkaido, these board builders tended to favour designs that suited powder – long, pointed noses, cutaway tails and the sorts of shapes seen on those early, surf-inspired American models.

Not only that, they were brilliant for carving, and boasted more muted, mature graphics. These were boards that your average older rider, whose knees were no longer up to knuckling kickers, could appreciate. Led by early adopters like Korua Snowboards, and Jeremy Jones, whose iconic Hovercraft model owes an obvious debt to Gentemstick, western brands began producing a whole new wave of Japanese-inspired surf shapes.

“It’s really funny to see how it’s moved from the U.S., to Europe, to Japan, in terms of the influence of things,” says Thierry. “That new spirit they brought was definitely the thing that influenced a lot of people.”

Forward to the Future

What’s next for snowboard designers? Well, answering the existential threat of climate change presents a huge challenge. According to Antoine Floquet, the designer behind the Apo board that Sage Kotsenberg rode to Olympic glory, the holy grail is “a fully recyclable snowboard,” but that’s still “about five to ten years away”. There have been steps in the right direction however.

Mervin Manufacturing, the people behind Lib Tech and Gnu boards, have spent years developing more environmentally friendly materials, and since acquiring the old Elan Snowboards Factory in Austria (which they’ve rebranded as The Mothership) Capita have transformed the facility, allowing it to run on 100% renewable energy. As Mark Dangler explains, “we believe we all need to take steps to protect the health and longevity of our winters.”

Assuming the snow lasts however, the future is looking brighter than it has in a long while. Thierry remembers “a golden age of snowboarding creativity” from the mid-80s to the mid-90s. “Every brand had a raceboard, boardercross board, freestyle board, an all round board,” and it was that variety that made the sport – and the job of designing gear for it – special.

The one-size-fits-all model that followed 10 years later was, he believes, a huge mistake. “It’s like asking Hamilton in Formula 1 to take a fucking Twingo, and see if he can win the Grand Prix, you know?” The point isn’t even that ‘quiver of one’ all mountain boards were bad, just that the lack of variety was restrictive. Or as he puts it, “the Twingo is fine, but for one thing. The Formula 1 car is for another. You can’t ask your mum and dad to do the shopping in a Formula 1 car.”

But as variety returns to the halls of ISPO, designers channel influences from North America, Europe and Japan, and manufacturers draw on the best traditions of skate, ski and surfboard making, snowboard manufacturing is, Thierry believes, “coming into a new golden age”.

These boards might look as retro as a beige iPhone with a rainbow-striped logo, but underneath, they’re the product of 40 years of design development. Just make sure, when you get your hands on one, that you don’t start touching it more than 2,000 times in a day. Because then you really would have a problem.